Developer: Freaky Creations

Publisher: Red Deer Games

Platform: Switch, PS4, PC

Tested on: Switch

To Leave (Switch) – Review

In recent years, we’ve seen more and more games that aren’t afraid to tackle mental health issues. It is of course important to normalize talking about things like anxiety and depression, and video games have proven to be an excellent medium to bring these themes into the public consciousness. The majority of games that deal with mental health as a primary theme, like Into A Dream or Stilstand, try to make the subject matter palatable but there are the occasional titles that are more heavy-handed and even incorporate trigger warnings before the game’s opening credits, like Doki Doki Literature Club or To Leave, which happens to be the subject of today’s review. We’ve taken a look at the PC version back in 2018 but with the game’s recent arrival on Switch and PS4, it seemed like a good idea to revisit Freaky Creations’ platformer.

Story

Protagonist Harm -what’s in a name?- is a young man suffering from manic depression, after his beloved commits suicide. The opening cutscene depicts how Harm has locked himself in his apartment, hiding from the outside world and finding refuge in his thoughts as he questions everything about his life. He lives his life in a dream-like state, and the only escape is through a magical door into his own mind. As it turns out, this door is the key to getting out of his current situation. The narrative that unfolds definitely warrants the trigger warning that is shown when you boot up the game. As much of its impact is lost if we were to spoil it, we’re going to refrain from actually giving away too much of what happens. Most of it isn’t told directly through cutscenes but actually needs to be read in Harm’s diary, which we felt was a bit of an odd choice, as it’s easy to skip or miss parts of the narrative this way. It also doesn’t really help that the actual diary entries weren’t written very well, though whether this is “in character” for Harm or because the writer isn’t a native English speaker is never made clear.

Graphics

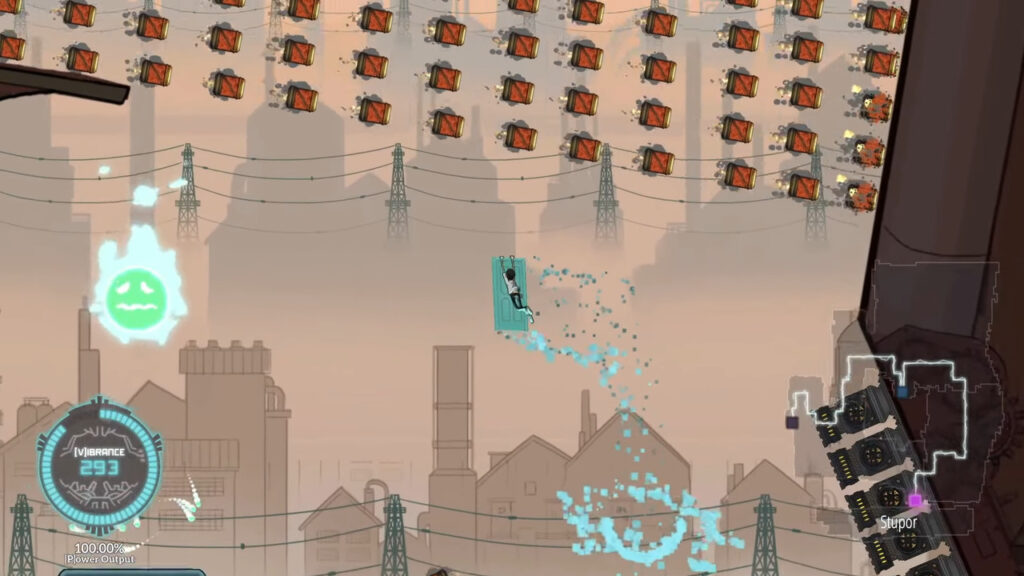

Set across ancient temples inhabited by fairies and strange gods, To Leave’s visuals turned out to be far more colorful than what we initially expected from the opening cutscene. The game is a visual treat, combining hand-drawn animation with trippy art direction and level designs where it’s never clear which way is up and which way is down. As a metaphor for the depressed mind, it works surprisingly well, despite the bright colors that we typically don’t associate with depression. The juxtaposition of the drab ‘real’ world, which we see in a few cutscenes, further drives this point home.

Sound

Accompanying To Leave’s surprisingly impressive visuals is a soundtrack that we’d describe as unsettling. The music sounds dark and mysterious, often even ethereal. The OST definitely takes front and center stage here, as the sound effects are unremarkable and voice acting is non-existent.

Gameplay

When we first learned that To Leave was a platformer, we were somewhat confused, as we couldn’t quite wrap our heads around the idea of combining classic platforming gameplay with the heavy topic of the game. As it turned out, our confusion wasn’t entirely unwarranted as the gameplay doesn’t quite mesh with the game’s overall atmosphere. Using his magical flying door, Harm must navigate the Dark Void and activate a series of temples. Once these are all activated, this will unify the Origin Gate and bring inner peace to our protagonist. Conceptually, it’s a brilliant way to depict Harm’s internal struggle, even if it’s a bit absurd, but in practice, you’re essentially playing what feels like a souped-up version of Flappy Bird, the hit mobile game from 2013. Granted, there is a bit more depth to be found here, but the core of To Leave’s gameplay is still built around carefully timing button taps in order to stay airborne and avoid obstacles, albeit in more than one direction. Perhaps a better comparison is the swimming mechanics from 2D Mario platformers, although To Leave‘s controls don’t feel as refined.

The individual levels are linear affairs and players take control of the door rather than Harm himself. Said door uses something called Vibrance as its source of energy. Vibrance depletes over time and is restored by picking up glowing orbs that are scattered throughout the levels. Crashing into obstacles doesn’t immediately mean game over, but when you do so, you’ll lose a significant chunk of Vibrance, and when you run out, that’s when your run ends. Levels are reasonably lengthy, and it’s unlikely that you’ll successfully navigate them to the end on the first try. To Leave seems to rely on you memorizing the locations of Vibrance orbs and checkpoints -which you’ll need to activate before you can actually use them. Once you manage to make it through to the temple at the end of a level, Harm then activates it. This drains him of his energy, turning him into a zombie-like creature for a short while, requiring him to rest. This state doesn’t really affect gameplay and is there as a metaphor for the drain that Harm’s depression has on him -or at least that’s how we interpreted it.

To Leave isn’t a very long game. Even taking into account that you’ll probably need multiple attempts to get through the later levels, you’re still looking at between just two and three hours before the end credits roll. It is priced accordingly and doesn’t overstay its welcome. Whether or not To Leave succeeds in what it sets out to do is something we’re still not sure about because it isn’t really clear what it wants to be in the first place. The gameplay is solid but unremarkable and most of To Leave’s merit lies in how it handles the overarching theme of dealing with depression. Even after having completed the game, we weren’t entirely sure who To Leave is for: it doesn’t offer any answers for those wanting to learn more about what depression is like, perhaps because they want to understand the struggles of a loved one, nor does it seem like it would be helpful for those that are actually suffering from it. The gameplay feels disconnected from the story as well, and we couldn’t help but feel that Harm’s story was perhaps best suited for a different medium than a video game, like a short film or a graphic novel. That’s not to say that this is a bad game per se, but it’s not a good one either: it simply exists.

Conclusion

We cannot stress how important it is to make topics like mental health or depression discussable. Video games are an excellent medium for this, as we’ve seen through various titles in the past. We wish that we could say that To Leave was one of those games, but ultimately, it left us feeling indifferent. That’s not a good thing, given that we can actually see the importance of the story it attempts to tell. For what it’s worth, the storytelling is good, even if the written text could use some polishing. It’s when we factor in the gameplay that To Leave devolves from what could have been a genuinely interesting take on a game with a depressed protagonist, into a bland and unexciting affair. Perhaps this was intentional, in an effort to convey Harm’s own feelings of indifference towards the world, but if it was, To Leave fails to get that point across.

No Comments